What’s a metatile? Just a fancy word for a block of tiles. 2×2 in my case. Why use them? It’s a form of compression. And it simplifies the BG. And the BG palette table (attribute table) can’t modify each tile’s palette selection, only a 2×2 block of tiles, at minimum.

Instead of thinking of a room as 32×30 tiles (960 bytes), the code will treat it like 16×15 metatiles (an array of 240 bytes). We only need 4 bits from X and 4 bits from Y to calculate the offset into a collision array.

index = (y & 0xf0) + (x >> 4);

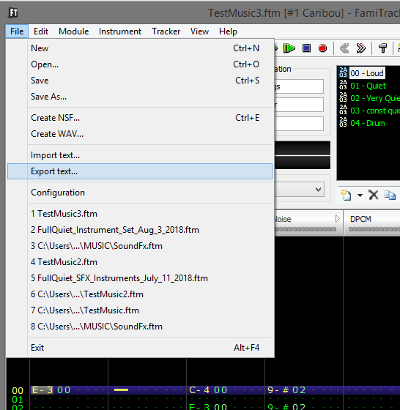

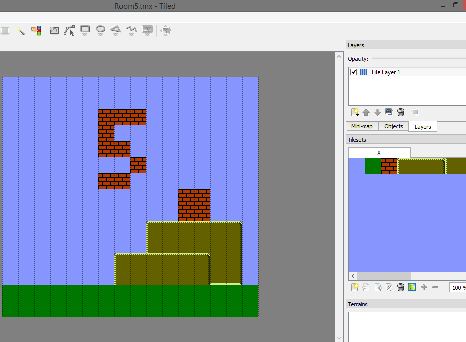

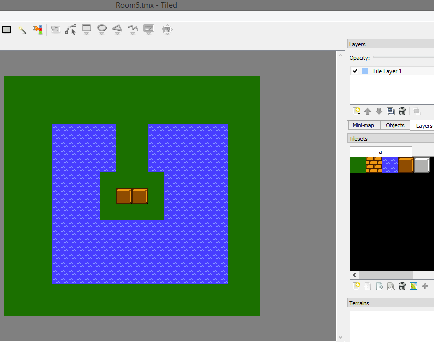

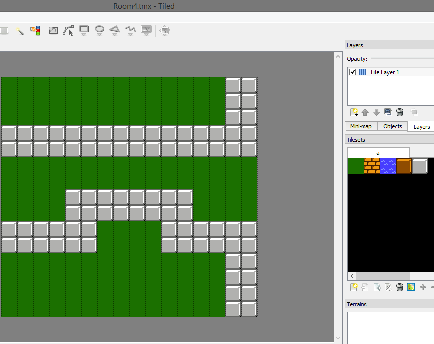

But, I take it one step further. The collision map can double as an array to draw the BG. I use a system, which allows me to use Tiled Map Editor to draw my levels. Rooms of size 16×15.

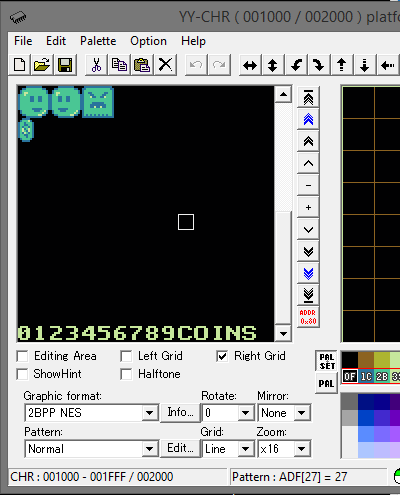

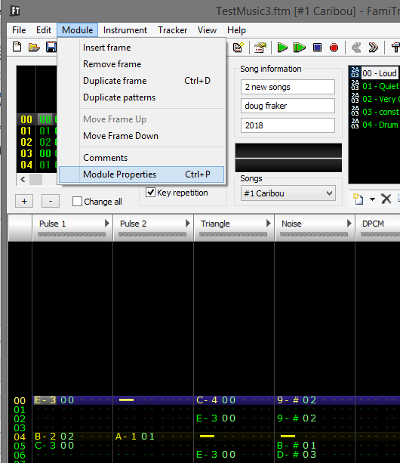

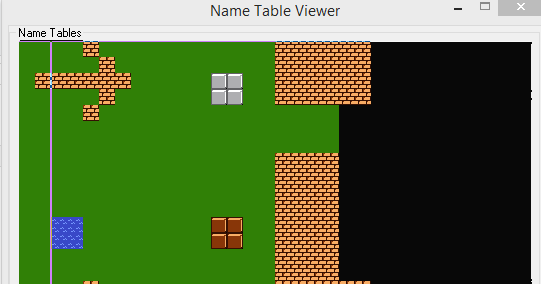

But we have to jump through some hoops to make this happen. We can’t draw our graphics in Tiled. The game graphics need to be 2bpp binary CHR files. We could make our graphics in a tile editor. I still recommend YY CHR to start. Then, import the graphics to NES Screen Tool. Then make some 16×16 blocks (2 tiles x 2 tiles) this is a good size because this is the size of the attribute table squares. And, importantly, choosing a palette for each block. If have 2 identical blocks of different color, I make them into 2 different metatiles (see the last 2 blocks… identical tiles, but different palette).

Start at the top left and make 16×16 blocks, which are our metatile blocks. My system can only handle 51 metatiles, because it assumes a data set under 256 bytes, and each metatile takes 5 bytes for definition. 51×5 = 255. The latest versions of NES Screen Tool (and NEXXT) can export the nametable as a BMP. This can be imported into Tiled, as a tileset, with the tile dimensions set to 16×16.

(I had to make the tile size in Tiled 32×32 because I actually made a screenshot of NES Screen Tool, and it doubles the pixel dimensions, and saved it as metatiles.png in the BG folder).

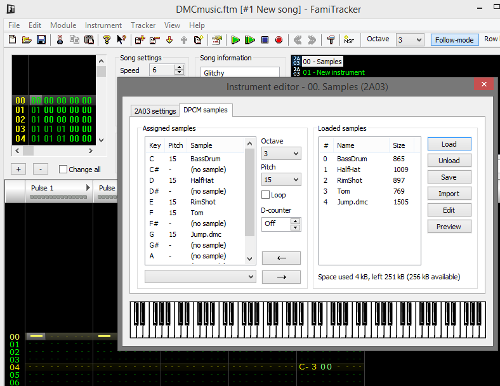

We’re not done with NES Screen Tool yet. Save as a nametable with attributes, uncompressed binary as a .nam file. Use my meta.py (python 3 script) to convert it into a c array. Here’s what it output…

const unsigned char metatiles[]={

2, 2, 2, 2, 3,

4, 4, 4, 4, 1,

9, 9, 9, 9, 2,

5, 6, 8, 7, 1,

5, 6, 8, 7, 0

};

4 tiles + 1 palette = 5 bytes per metatile. I copy this array into the code.

Now, to Tiled, and make my level data. It’s a nice GUI for designing video game levels. We imported the metatiles.png as the tileset. And drew our level.

Make a level. Save it. Then, export to csv file. you could easily turn that into a c array, but I made a .py file to automate that step, csv2c.py, and turn our csv file to a C array, “Room1.c”. Import that into the game.

.

How does the metatile system work?

Ok. we have our metatile data. we have our level data. How does the metatile system work?

So my metatile system is an extension of the vram buffer system. It can run while the screen is on, but in this example it writes while the screen is off. Instead of waiting for NMI to push our data to the ppu, we’re going to speed up everything by immediately pushing the vram buffer to ppu with flush_vram_update2(). I guess flush usually means empty the buffer, but for this code it means “send it right away”.

I already set up a pointer to the vram buffer… set_vram_buffer(). Also, we need to set a pointer to the metatile definitions set_mt_pointer(metatiles1), and set a pointer to the room data set_data_pointer(Room1). Now we can use the metatile functions.

I made 2 functions for pushing metatiles to the buffer.

buffer_1_mt(address, metatile); // push 1 metatile, no palette changes. (this doesn’t need a pointer to the room data). We could have used this if we read each byte off the room array, and sent that byte as the metatile #. But, you can also use this anytime to change 1 metatile on the screen. However, this function does not send the palette information. I didn’t make it smart enough to modify the attribute table.

buffer_4_mt(address, index); // push 4 metatiles (2×2 block) and set their palettes. Index is the index into the room data array. It actually finds 4 metatile blocks in the room, and pushes each to the vram buffer. This function also sets the attribute table, and you should use this one to load the level.

The room loader code does a loop, and goes to every 32 x 32 pixel block, and converts all the data to metatiles, and prints them to the screen.

for(y=0; ;y+=0x20){

for(x=0; ;x+=0x20){

address = get_ppu_addr(0, x, y);

index = (y & 0xf0) + (x >> 4);

buffer_4_mt(address, index); // ppu_address, index to the data

flush_vram_update2();

if (x == 0xe0) break;

}

if (y == 0xe0) break;

}

flush_vram_update2() immediately pushes to the ppu, so the screen needs to be off.

I updated the movement / BG collision code (Feb 2023). We are checking 2 points for X (either 2 on the right, if moving right… or 2 on the left, if moving left). We eject if collision X. Then we check 2 points for Y (either top or bottom) and eject if collision.

The hitbox is actually 13×13 instead of 15×15, so that he can slide into smaller spaces a little better. If you had a large metasprite, bigger than 16×16, you might have to check 3 or more points per side.

We are still colliding with the c_map ( = collision map). Every non zero metatile is solid. This could be improved, so that each bit represents some property of the tile. But for now, lets just say that != 0 means solid.

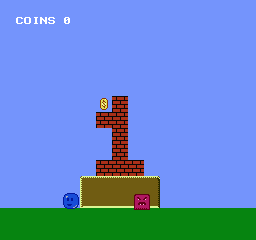

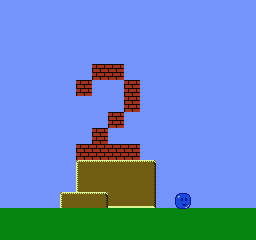

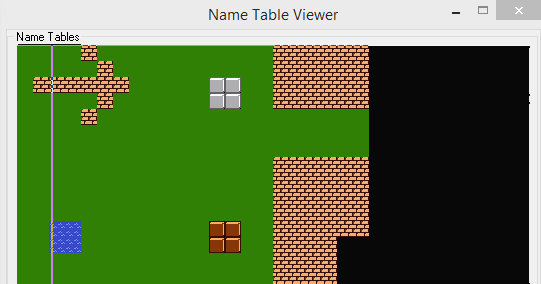

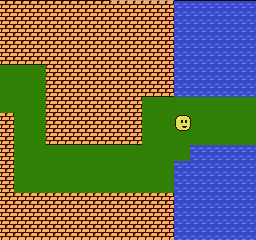

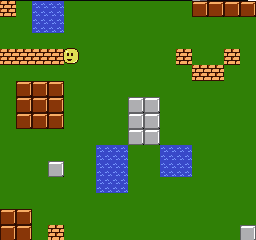

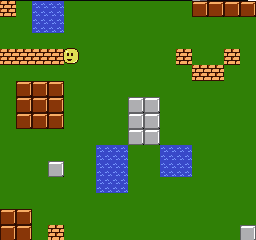

Here’s what the game looks like, and he’s colliding nicely.

https://github.com/nesdoug/13_Metatiles/blob/master/metatiles.c

https://github.com/nesdoug/13_Metatiles

.

.

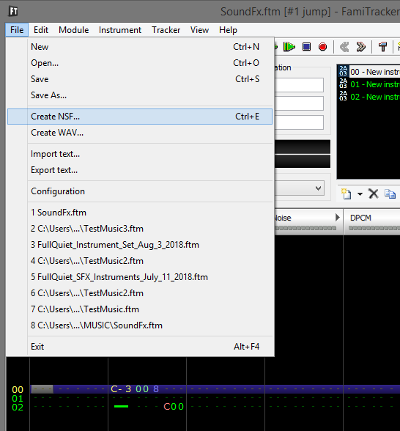

Example 2

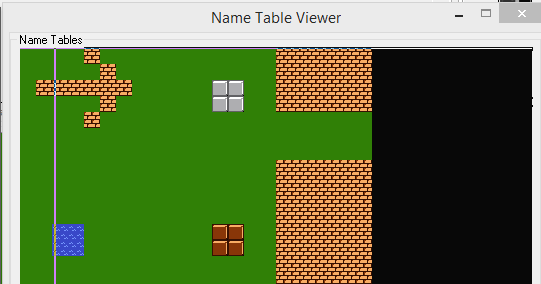

And then I made another one, because I wanted to show how buffer_1_mt() worked. It’s basically the same code as the last time… I did have to change the main BG color to green to get this to work how I wanted.

buffer_1_mt() is supposed to be for changing a metatile mid-game. But it doesn’t affect palettes. Changing just 1 metatiles worth of palettes would require changing just 2 bits of a byte of the attribute table, and doing that is quite annoyingly complicated.

buffer_1_mt() requires that you turn on the vram system, set_vram_buffer(), and it needs a pointer set for the metatile definitions set_mt_pointer(metatiles). You just need to give it an address, and tell it which metatile you want to print there.

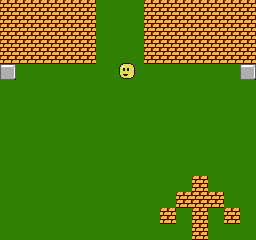

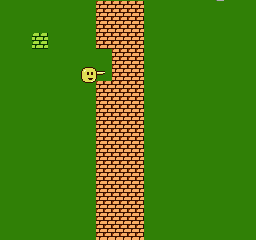

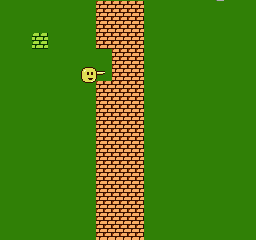

This was the level data.

.

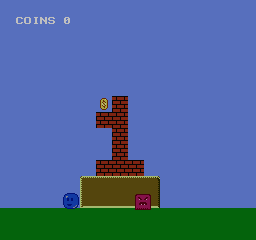

And I added just 1 more metatile using buffer_1_mt() at the top left.

buffer_1_mt(NTADR_A(4,4),1);

The right parameter (1) means put the #1 metatile (brick), with it’s top left tile starting at 4th tile from the left and 4th tile from the top.

Notice its palette is wrong. buffer_1_mt() doesn’t change attribute bytes. You could fix this, if you knew which bits to send. I don’t want to get into that, but if you uncomment these lines in the code, it would color that block correctly.

address = get_at_addr(0, 32, 32); // tile 4,4 = pixels 32,32

one_vram_buffer(0x01,address); // top left = palette 1

I gave the little guy a stick, which pokes to the right if you press A or B. When the stick is out, it checks the collision map to see if there is a block there, and replaces it with blank blocks using the one_vram_buffer() function. (and also changes the collision map byte to zero, so you can walk through it).

void break_wall(void){

temp_x = BoxGuy1.x >> 8;

temp_x += 0x16;

temp_y = BoxGuy1.y >> 8;

temp_y += 5;

coordinates = (temp_x>>4) + (temp_y & 0xf0);

if(c_map[coordinates] == 1){ // if brick

c_map[coordinates] = 0; // can walk through it

address = get_ppu_addr(0, temp_x, temp_y);

buffer_1_mt(address, 0); // put metatile #0 here = blank grass

}

}

So the system is a bit complicated, but as you can see, the code is pretty straightforward.

https://github.com/nesdoug/14_Metatiles2/blob/master/metatiles2.c

https://github.com/nesdoug/14_Metatiles2

.

We could easily make a non-scrolling game, with just this. You would just need to make room data for each room, and call the room loader when you walk to the edge of the screen. Lot’s of games work like that.

But, I decided to make some scrolling examples, because ultimately, I want to make a platformer. Next time, we add scrolling.

.

.

More than 51 Metatiles

Someone asked me what to do if you need more than 51 kinds of metatiles, so, I made a version that can handle up to 256 metatiles. The nesdoug.s file is different, and does a 16 bit calculation to find the position of the metatile in the array. It’s not very fast, so this could be improved in the future.

(actually the limit is 240, for the way I’m making the metatiles in NES Screen Tool.)

https://github.com/nesdoug/13_Metatiles256

.

.